The Good Samaritan, a character Jesus created in one of his most famous parables, is so popular and admired that people have named numerous organizations after him in order to connect their own mission to this selfless man. Governments have enacted laws bearing that name to protect those who act courageously to help others. Throughout the centuries, artists have depicted this character, and songwriters have celebrated him.

I revere the story too, but it is not my favorite. I find it to be one of the most guilt-inducing stories in the Bible. How can I live up to the example of this man who gave so extravagantly? I try to be compassionate and generous, but won’t I always fall short of his level? What does Jesus expect from his followers who read this story?

Defining the word “neighbor” is what prompted Jesus to tell the story in the first place. A lawyer, who may or may not be trying to get a free pass from Jesus, asks Jesus, “Who is my neighbor?” Then comes the parable.

When people think of the Good Samaritan today, compassion is the attribute that most stands out. Good Samaritan laws, for example, protect those who take risks to help others in distress. But the story is also about breaking down barriers of ethnicity, race, religion, and other differences that divide people. For Jesus’s original audience, the shocking thing about the parable was that the Samaritan was the hero of the story. Samaritans weren’t supposed to be heroes. They were the enemy. They were looked down on. But this Samaritan acts as a neighbor. He crosses boundaries to do good. Jesus told the lawyer at the end of the parable, “Go and do likewise.”

The Samaritan is good, but his example is not at such a level that it should only make us feel guilty or paralyze us into inaction. He acts compassionately, but he is not expected to fix everything in order to be a neighbor. He doesn’t chase down the robbers and bring them to justice. He doesn’t create a police force to patrol that dangerous road. He doesn’t take responsibility for every victim of crime in that area. He doesn’t assume responsibility for the victim for the rest of his life. There are limits to his time and resources and capabilities, but he is considered the true neighbor because his impulse is love. He acts rather than make excuses. He does not let limitation, fear, prejudice, or rationalization stop him. He does what is in his power.

He acts rather than make excuses. He does not let limitation, fear, prejudice, or rationalization stop him. He does what is in his power.

It’s easy to read this parable and ask ourselves whether we measure up to the Good Samaritan. But at some point I find myself identifying with every character in the story. I have been the priest and Levite crossing the road when I see a person who needs me—either because I don’t care enough, or I’m busy, or I’m afraid, or I harbor unacknowledged prejudices that make me believe I should keep the needy person at a distance. I can relate to the innkeeper, faithfully carrying out my duty when the situation calls for it. I can identify with the crime victim, knocked into helplessness by tragedy, wondering who will rescue me and whether I will have the humility to accept that help. In my best moments I can identify with the Good Samaritan. I decide—at whatever cost—to follow that impulse deep within to act in love. Instead of fleeing the person who makes me cringe, I push myself toward that person and make their problems my own. I follow through until I see the situation set right. I willingly pay the price. I become a neighbor.

Jesus said, “Go and do likewise.”

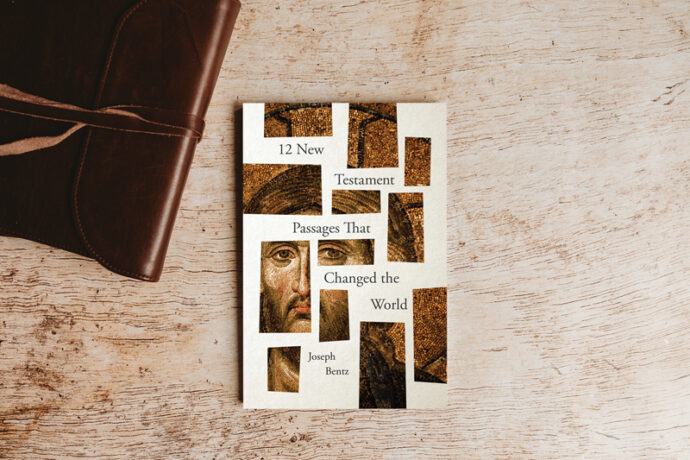

Read more from Joseph Bentz in his latest book, 12 New Testament Passages that Changes the World.

Read more from Joseph Bentz in his latest book, 12 New Testament Passages that Changes the World.

0 Comments